-

-

Notifications

You must be signed in to change notification settings - Fork 139

Spaced Repetition Algorithm: A Three‐Day Journey from Novice to Expert

I am Jarrett Ye, the principal author of the papers A Stochastic Shortest Path Algorithm for Optimizing Spaced Repetition Scheduling and Optimizing Spaced Repetition Schedule by Capturing the Dynamics of Memory. I am currently working at MaiMemo Inc., where I am chiefly responsible for developing the spaced repetition algorithm within MaiMemo's language learning app. For a detailed account of my academic journey leading to the publication of these papers, please refer to How did I publish a paper in ACMKDD as an undergraduate?

This tutorial, "Spaced Repetition Algorithm: A Three-Day Journey from Novice to Expert," is adapted from the manuscript I initially prepared for internal presentations at MaiMemo. The objective is to elucidate what exactly spaced repetition algorithms are investigating and to inspire new researchers to contribute to this field and advance the progress of learning technology. Without further ado, let us embark on this intellectual journey.

Since their school days, most students intuitively know the following two facts:

- Reviewing information multiple times helps us remember it better.

- Different memories fade at different rates, not all at once.

These insights raise further questions:

- How much knowledge have we already forgotten?

- How quickly are we forgetting it?

- What is the best way to schedule reviews to minimize forgetting?

In the past, very few people have measured these factors or used them to optimize their review schedules. The focus of spaced repetition algorithms is to understand and predict how we remember things and to schedule our reviews accordingly.

In the next three days, we will delve into spaced repetition algorithms from three perspectives:

- Empirical algorithms

- Theoretical models

- Latest progress

Today, we begin our journey by diving into the simplest yet impactful empirical algorithms. We'll uncover the details and the ideas that guide them. But first, let's trace the roots of a term that pervades this field — spaced repetition.

For readers new to the subject of spaced repetition, let's learn about the concept of the "forgetting curve."

After we learn something, whether from a book or a class, we start to forget it. This happens gradually, just like the forgetting curve that slopes downward.

The forgetting curve illustrates the way our memory retains knowledge. It exhibits a unique trajectory: in the absence of active review, memory decay is initially rapid and slows down over time.

How can we counteract this natural tendency to forget? Let's consider the effect of reviews.

Introducing periodic reviews flattens the forgetting curve, indicating a slower memory decay over time. In other words, it slows down the rate at which we forget information.

Now, a question arises: How can these review intervals be optimized for efficient memory retention?

Did you notice the varying lengths of the review intervals? Shorter intervals are used for unfamiliar content, while longer ones are employed for more familiar material, which scatters reviews over different timings in the future. This tactic, known as spaced repetition, augments the formation of long-term memories.

But how effective is it? Here are some studies that show the benefits of spaced repetition (source):

- Rea & Modigliani 1985, “The effect of expanded versus massed practice on the retention of multiplication facts and spelling lists”:

A test immediately following the training showed superior performance for the distributed group (70% correct) compared to the massed group (53% correct). These results seem to show that the spacing effect applies to school-age children and to at least some types of materials that are typically taught in school.

- Donovan & Radosevich 1999, “A meta-analytic review of the distribution of practice effect: Now you see it, now you don’t”:

According to Donovan & Radosevich’s meta-analysis of spacing studies, the effect size for the spacing effect is d = 0.42. This means that the average person getting distributed training remembers better than about 67% of the people getting massed training. This effect size is nothing to sneeze at-in education research, effect sizes as low as d = 0.2 are considered “practically significant”, while effect sizes above d = 1 are rare.

You might be thinking that if spaced repetition is so effective, why isn't it more popular?

The main obstacle is the overwhelming volume of knowledge that must be learned. Each piece of knowledge has its unique forgetting curve, which makes manual tracking and scheduling an impossible task.

This introduces the role of spaced repetition algorithms: automating the tracking of memory states and arranging efficient review schedules.

By now, you should have a basic understanding of spaced repetition. But some questions likely still linger, such as the calculation of optimal review timing and best practices for efficient spaced repetition. These questions will be answered in the coming chapters.

| Question | Answer |

|---|---|

| What aspect of memory does the forgetting curve capture? | The curve describes how knowledge retention decays over time in our memory. |

| How does memory retention decline in the absence of review? | It initially decreases rapidly and then slowly. |

| How does the forgetting curve change after a successful review? | The new curve is flatter, indicating a slower rate of forgetting. |

| How does spaced repetition accommodate the content with different familiarity levels? | Shorter intervals are applied for unfamiliar content, while longer ones are set for familiar material. |

| What is the role of algorithms in spaced repetition? | They automate the tracking of memory states and the arrangement of efficient review schedules. |

Having delved into the concept of spaced repetition, you may find yourself pondering over this guiding principle:

Shorter intervals are used for unfamiliar content, while longer ones are employed for more familiar material, which scatter reviews over different timings in the future.

What exactly defines these 'short' or 'long' intervals? Furthermore, how can one distinguish between material that is 'familiar' and that which is 'unfamiliar'?

Intuitively, we know that the slower we forget the material, the more familiar it is, and so we can use longer intervals for more familiar material. But the less we want to forget, the shorter the interval should be. The shorter the interval, the higher the frequency of reviews.

It seems that there's an inherent contradiction between the frequency of reviews and the rate of forgetting. On the one hand, we want to do more reviews to remember more. On the other hand, we don't need to review familiar material very often. How do we solve this dilemma?

Let's take a look at how the creator of the first computational spaced repetition algorithm set out on his journey in the exploration of memory.

In 1985, a young college student named Piotr Woźniak was struggling with the problem of forgetting:

The above image shows a page from his vocabulary notebook, which contained 2,794 words spread across 79 pages. Each page had about 40 pairs of English-Polish words. Managing all those reviews was a headache for Wozniak. At first, he didn't have a systematic plan for reviewing the words; he just reviewed whatever he had time for. But he did something crucial: he kept track of when he reviewed and how many words he forgot, allowing him to measure his progress.

He compiled a year's worth of review data and discovered that his rate of forgetting ranged between 40% and 60%. This was unacceptable to him. He needed a reasonable study schedule that would lower his forgetting rate without overwhelming him with reviews. To find an optimal review interval, he commenced his memory experiments.

Wozniak wanted to find the longest possible time between reviews while keeping the forgetting rate under 5%.

Here are the details about his experiment:

Material: Five pages of English-Polish vocabulary, each with 40 word pairs.

Initial learning: Memorize all 5 pages of material. Look at the English word, recall the Polish translation, and then check whether the answer is correct. If the answer is correct, eliminate the word pair from this stage. If the answer is incorrect, try to recall it later. Keep doing this until all the answers are correct.

Initial review: A one-day interval was employed for the first review, based on Wozniak's previous review experience.

The ensuing key stages — A, B, and C — revealed the following:

Stage A: Wozniak reviewed five pages of notes at intervals of 2, 4, 6, 8, and 10 days. The resulting forgetting rates were 0%, 0%, 0%, 1%, and 17%, respectively. He determined that a 7-day interval was optimal for the second review.

Stage B: A new set of five pages was reviewed after 1 day for the first time and then after 7 days for the second time. For the third review, the intervals were 6, 8, 11, 13, and 16 days, with forgetting rates of 3%, 0%, 0%, 0%, and 1%. Wozniak selected a 16-day interval for the third review.

Stage C: Another fresh set of five pages was reviewed at 1, 7, and 16-day intervals for the first three reviews. For the fourth review, the intervals were 20, 24, 28, 33, and 38 days, with forgetting rates of 0%, 3%, 5%, 3%, and 0%. Wozniak opted for a 35-day interval for the fourth review.

During his experiments, he noticed that the subsequent optimal interval was approximately twice as long as the preceding one. Finally, he formalized the SM-0 algorithm on paper.

- I(1) = 1 day

- I(2) = 7 days

- I(3) = 16 days

- I(4) = 35 days

- for i>4: I(i) = I(i-1) * 2

- Words forgotten in the first four reviews were moved to a new page and cycled back into repetition along with new materials.

Here,

The goal of the SM-0 algorithm was clear: to extend the review interval as much as possible while minimizing the rate of memory decay. Its limitations were evident as well, namely its inability to track memory retention at a granular level.

Nonetheless, the effectiveness of the SM-0 algorithm was evident. With the acquisition of his first computer in 1986, Wozniak simulated the model and drew two key conclusions:

- Over time, the total amount of knowledge increased instead of decreasing

- In the long run, the knowledge acquisition rate remained almost unchanged

These insights proved that the algorithm can achieve a compromise between memory retention and the frequency of review. Wozniak realized that spaced repetition didn't have to drown learners in an endless sea of reviews. This realization inspired him to continue refining spaced repetition algorithms.

| Questions | Answers |

|---|---|

| Which two factors did Wozniak consider for determining optimal review intervals? | Interval length and the rate of memory decay, associated with memory retention. |

| Why did Wozniak use new materials each time he sought to establish a new review interval in his experiments? | To ensure uniformity in the intervals of prior reviews, thus controlling for variables. |

| What is the primary limitation of the SM-0 Algorithm? | It uses a page of notes as the unit for review, making it unsuitable for tracking memory retention at a more granular level. |

Though the SM-0 algorithm proved to be beneficial to Wozniak's learning, several issues prompted him to seek refinements:

-

If a word is forgotten at the first review (after 1 day), it will be more likely to be forgotten again during the subsequent reviews (after 7 and 16 days) compared to words that were not forgotten before.

-

New note pages composed of forgotten words have a higher chance of being forgotten even when the review schedule is the same.

The first observation made him realize that reviewing doesn't always make him more familiar with the material, and the speed of forgetting doesn't slow down. If he keeps reviewing these words with longer gaps like the rest on the same note page, it won't work well.

The second observation made him realize that not all material is equally hard. Materials with different difficulty levels should have different review intervals.

Consequently, in 1987, after getting his first computer, Wozniak utilized his two-year record and insights from the SM-0 algorithm to develop the SM-2 algorithm. Anki's built-in algorithm is a variation of the SM-2 algorithm.

The details about SM-2:

- Break down the information you want to remember into small question-answer pairs.

- Use the following intervals (in days) to review each question-answer pair:

-

$I(1) = 1$ -

$I(2) = 6$ -

For

$n > 2$ ,$I(n) = I(n-1) \times EF$ -

$EF$ —the Ease Factor, with an initial value of 2.5 - After each review,

$\text{newEF} = EF + (0.1 - (5-q) \times (0.08 + (5-q) \times 0.02))$ -

$\text{newEF}$ —the post-review updated value of the Ease Factor -

$q$ —the quality grades of review, ranging from 0 - 5. If it's >= 3, it means the learner remembered, and if it's < 3, the learner forgot.

-

-

-

If the learner forgets, the interval for the question-answer pair will be reset to

$I(1)$ with the same EF.

-

The SM-2 algorithm adds the review feedback to how often you review the question-answer pairs. The lower the EF, the smaller the interval multiplier factor; in other words, the slower the intervals grow.

The SM-2 algorithm was still based on Wozniak's experimental data, but it has two main strengths that make it a popular spaced repetition algorithm even today:

-

It breaks the material down into small question-answer pairs. This lets the review schedule be super specific to each pair and separates the review schedules of hard and easy material sooner.

-

It uses an "Ease Factor" and grades. So, the algorithm can modify the learner's future reviews based on how well the learner remembers the material.

| Questions | Answers |

|---|---|

| Why shouldn't we set a longer interval for material we forgot during a review? | The speed of forgetting doesn't slow down for that material; in other words, the forgetting curve doesn't get flatter. |

| What shows that some material is harder to remember than others? | The pages with material that was forgotten had a higher chance of being forgotten again. |

| What is the practical purpose of incorporating an "Ease Factor" and grades into the SM-2 algorithm? | This enables the algorithm to dynamically adjust future review intervals based on user performance. |

| What are the advantages of breaking material down into smaller parts for review? | It lets the algorithm separate the easy material from the hard material sooner. |

The primary objective of SM-4 is to improve the adaptability of its predecessor, the SM-2 algorithm. Although SM-2 can fine-tune the review schedules for individual flashcards based on ease factors and grades, these adjustments are made in isolation, without regard to prior changes made to other cards.

In other words, SM-2 treats each flashcard as an independent entity, remaining uninformed about the user's overall learning process. To overcome this, SM-4 introduces an Optimal Interval (OI) Matrix, replacing the existing formulas used for interval calculations:

In the Optimal Interval (OI) matrix, the rows depict how easy the material is and the columns depict how many times you've seen it. Initially, the entries in the matrix are filled using the SM-2 formulas that decide how long to wait before reviewing a card again.

To allow new cards to benefit from the adjustment experience with old cards, the OI matrix is continuously updated during the reviews. The main idea is that if the OI matrix says to wait X days and the learner actually waits X+Y days and still remembers with a high grade, then the OI value should be changed to something between X and X+Y.

The reason for this is simple: if the learner can remember something after waiting X+Y days and get a good score, then the old OI value was probably too short. Let's make it longer!

This simple idea allowed SM-4 to become the first algorithm capable of making adjustments based on the learner's experience. But it didn't work as well as Wozniak had hoped, for the following reasons:

- Each review only changes one entry of the matrix, so it takes too long to improve the entire OI matrix.

- For longer review intervals, gathering enough data to fill the corresponding matrix entry takes a long time.

To address these issues, the SM-5 algorithm was designed. But I won't go into details here because of space limits.

| Question | Answer |

|---|---|

| Why is the adaptability of the SM-2 algorithm limited? | Adjustments to each flashcard's schedule are made in isolation, the algorithm doesn't "see" the user's memory as a whole. |

| What components does SM-4 introduce to enhance adaptability? | Optimal Interval Matrix and dynamic interval-adjustment rules. |

| What is the underlying principle for interval adjustments in SM-4? | If the learner exhibits good recall over extended intervals, the original interval should be longer, and vice versa. |

First discovered in 1885, the forgetting curve shows how we remember and forget. Fast-forward to 1985, when the first computer algorithm for spaced repetition aimed at finding the optimal review schedule was developed. This section has outlined the developmental progression of empirically based algorithms:

- SM-0 gathered experimental data to determine the best review intervals for a given individual and a specific type of material (Wozniak defined what "best" means here).

- SM-2 digitalized the algorithm for computer applications, introducing a more granular card level and incorporating adaptive ease factors and grades.

- SM-4 further enhanced the adaptability of the algorithm for a diverse range of learners, introducing the Optimal Interval Matrix along with rules for adjusting the intervals.

Although the empirical observations offer a valuable lens through which to understand spaced repetition, it's hard to improve them without a sound theoretical understanding. Next, we'll be diving into the theoretical aspects of spaced repetition.

Spaced repetition sounds like a theoretical field, but I've spent a lot of time discussing empirical algorithms. Why?

Because without the foundational support of empirical evidence, any theoretical discourse would be without merit. Our gut feelings about the behavior of the human memory may not be accurate. So, the theories we'll discuss next will also start from what we've learned so far to ensure that they are grounded in reality.

Here's a question to ponder: what factors would you consider when describing the state of a material in your memory?

Before Robert A. Bjork, many researchers used memory strength to talk about how well people remembered something.

Let's revisit the forgetting curve for a moment:

Firstly, memory retention (recall probability) emerges as a pivotal variable in characterizing the state of one's memory. In our everyday life, forgetting often manifests as a stochastic phenomenon. No one can unequivocally assert that a word memorized today will be recalled ten days later or forgotten twenty days later.

Is recall probability sufficient to describe the state of memory? Imagine drawing a horizontal line through the forgetting curves above; each curve will be intersected by the horizontal line at a point with the same probability of recall, yet the curves are different.

Relying solely on recall probability does not allow us to distinguish the rate of forgetting associated with different materials. However, this rate should certainly be factored into the description of memory states.

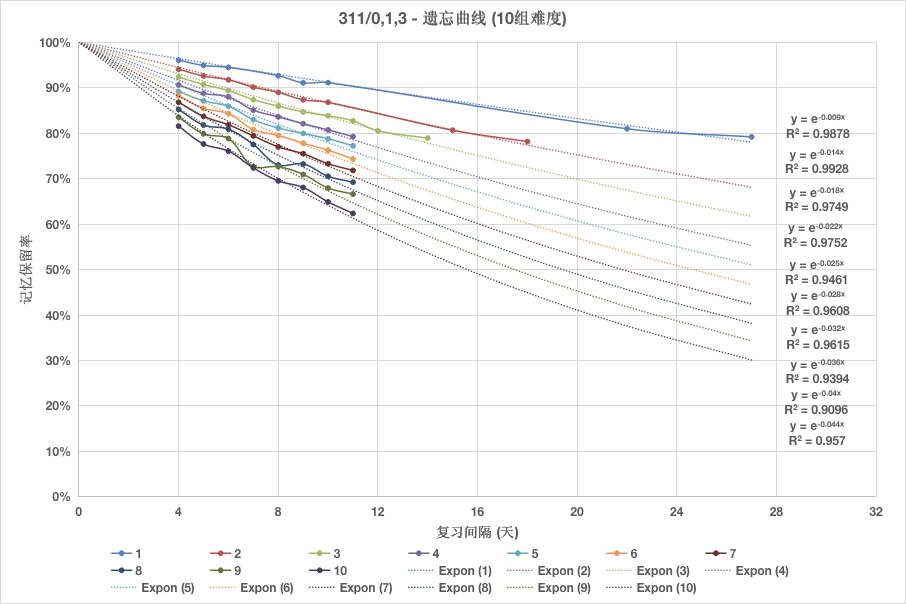

To address this problem, we must delve into the mathematical properties of the forgetting curve — a task that requires a large amount of data for plotting the curve. The data in this tutorial is sourced from an open dataset created by the language learning application MaiMemo.

From the figure above, we find that the forgetting curve can be approximated by a negative exponential function. The rate of forgetting can be characterized by the decay constant of this function.

We can write the following equation to obtain a fitting formula for the forgetting curve:

In this equation,

The relationship between

Memory stability,

The two components of memory proposed by Bjork — retrieval strength and storage strength — correspond precisely to recall probability and memory stability defined here.

The equation yields the following observations:

-

When

$t=0$ ,$R=100%$ , meaning that immediately after successful recall, the process of forgetting has not yet begun, and the probability of recall is at its maximum value of 100%. -

As

$t$ approaches infinity,$R$ approaches zero, meaning that if you never review something, you will eventually forget it. -

The first derivative of the negative exponential function is decreasing (i.e., the second derivative is negative). This is consistent with the empirical observation that forgetting is fast initially and slows down subsequently.

Thus, we have defined two components of memory, but something seems to be missing.

When the shape of the forgetting curve changes after review, the memory stability changes. This change doesn't depend only on the recall probability at the time of the review and the previous value of memory stability.

Is there evidence to substantiate this claim? Think about the first time you learn something: your memory stability and probability of recall are both zero. But after you learn it, your probability of recall is 100%, and the memory stability depends on a certain property of the material you just learned.

The thing you're trying to remember itself has a property that can affect your memory. Intuitively, this variable is the difficulty of the material.

After including the difficulty of the material, we have a three-component model of memory.

| Question | Answer |

|---|---|

| Why can't a single variable of memory strength adequately describe the state of memory? | A single variable is insufficient because the forgetting curve encompasses both retention levels and the rate of forgetting. |

| What variable measures the degree of memory retention? | Recall probability |

| Which function can approximate the forgetting curve? | Exponential function |

| What variable measures the speed of forgetting? | Decay constant |

| What is the definition of memory stability? | The time required for the recall probability to decline from 100% to a predetermined percentage, often 90%. |

Let us delve into the terms:

- Stability: The time required for the probability of recall for a particular memory to decline from 100% to 90%.

- Retrievability (probability of recall): The probability of recalling a specific memory at a given moment.

- Difficulty: The inherent complexity associated with a particular memory.

The difference between retrievability and retention is that the former refers to the probability of recalling a particular memory, whereas the latter refers to the average recall probability for a population of memories.

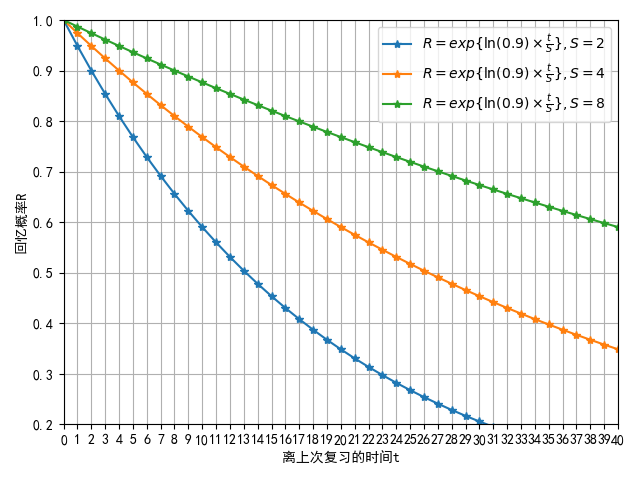

With the above terms, one can define the retrievability of any given memory at time

By transforming

Where:

-

$I_1$ denotes the interval before the first review. -

$C_i$ represents the ratio between the$i$ -th review interval and the preceding$i-1$ -th review interval.

The objective of spaced repetition algorithms is to accurately compute

To recap, both SM-0 and SM-2 algorithms have an

A question to ponder is: what is the relationship between

Below are some empirical observations from Wozniak, corroborated by data from vocabulary learning platforms like MaiMemo:

- Impact of stability: A higher

$S$ results in a smaller$C_i$ . This means that as memory becomes more stable, its subsequent stabilization becomes increasingly hard. - Impact of retrievability: A lower

$R$ results in a larger$C_i$ . This means that a successful recall at a low probability of recall leads to a greater increase in stability. - Impact of difficulty: A higher

$D$ results in a smaller$C_i$ . This means that the higher the complexity of the material, the smaller the increase in stability after each review.

Due to the involvement of multiple factors,

For the sake of subsequent discourse, we shall adopt SM-17's terminology for

Let us now delve into a more detailed discussion of stability increase.

| Question | Answer |

|---|---|

| Which variables are encapsulated in the three-component model of memory? | Memory stability, memory retrievability, and memory difficulty. |

| What differentiates retrievability from retention rate? | The former pertains to individual memories, whereas the latter refers to large populations of memories. |

| What two values connect the three-component model of memory and spaced repetition algorithms? | The initial review interval |

| What is |

Stability increase |

In this chapter, we will ignore the influence of memory difficulty and focus just on the relationship between memory stability increase (SInc), stability (S), and retrievability (R).

Data for the following analysis was collected from SuperMemo users and analyzed by Wozniak.

Upon investigating the stability increase (SInc) matrix, Wozniak discovered that for a given level of retrievability (R), the function of SInc with respect to stability (S) can be approximated by a negative power function.

By taking the logarithm of both stability increase (Y-axis) and stability (X-axis), the following curve is obtained:

This supports our prior qualitative conclusion, "As S increases,

As predicted by the spacing effect, stability increase (SInc) is greater for lower values of retrievability (R). After analyzing multiple datasets, it was observed that SInc demonstrates exponential growth as R diminishes.

Upon taking the logarithm of retrievability (X-axis), the following curve is obtained:

Surprisingly, SInc may fall below 1 when R is 100%. Molecular-level research suggests that memory instability increases during review. This once again proves that reviewing material too often is not beneficial to the learner.

Based on the above observations, we can deduce more interesting conclusions through combinations, changing perspectives, etc.

As time (t) increases, retrievability (R) decreases exponentially, while Stability Increase (SInc) increases exponentially. These two exponents counterbalance each other, yielding an approximately linear curve.

There are several criteria for the optimization of learning. One can target specific retention rates or aim to maximize memory stability. In either case, comprehending the expected stability increase proves advantageous.

We define the expected stability increase as:

This equation produces an interesting result: the maximum value of expected stability increase occurs when the retention rate is between 30% and 40%.

It's crucial to note that the maximum expected stability increase does not necessarily equate to the fastest learning rate. For the most efficient review schedule, refer to the forthcoming SSP-MMC algorithm.

| Question | Answer |

|---|---|

| What mathematical function describes the relationship between stability increase and memory stability? | Negative power function |

| What mathematical function describes the relationship between stability increase and memory retrievability? | Exponential function |

Memory stability also depends on the quality of memory, termed here as memory complexity. For efficient review sessions, knowledge associations must be simple, even if the knowledge itself is complex. Flashcards can encapsulate complex knowledge architectures, yet individual flashcards should be atomic.

In 2005, Wozniak formulated an equation to describe the review of composite memories. He observed that the stability of a composite memory behaves similarly to resistance in a circuit. (*Note: Composite is used instead of complex to emphasize its composed nature of simpler elements.)

Composite knowledge yields two primary conclusions:

- Additional information fragments lead to interference. In other words, sub-memory A destabilizes sub-memory B, and vice versa.

- Uniformly stimulating the sub-components of the memory during review is very difficult.

Suppose we have a composite flashcard that requires the memorization of two fill-in-the-blank fields. Assume both blanks are equally challenging to remember. Hence, the retrievability of the composite memory is the product of the retrievabilities of its sub-memories.

Plugging this into the decay curve equation, we get

Here,

Leading to,

Remarkably, the stability of a composite memory will be lower than the stabilities of each of its constituent memories. Also, the stability of the composite memory will be closer to the stability of the more challenging sub-memory.

As the complexity increases, memory stability approaches zero. This means that there is no way to memorize an entire book as a whole except by continuously rereading it. This is a futile process.

| Question | Answer |

|---|---|

| What is the relationship between the retrievability |

|

| Can the stability |

The stability of a composite memory is lower than the stabilities of its components. |

| How does the stability of a composite memory change as the number of its constituent memories increases? | It progressively diminishes, asymptotically approaching zero. |

After learning some theories of memory, it's time to put them into practice. The upcoming section will introduce how these memory theories can be used to develop spaced repetition algorithms and improve the users' learning efficiency.

There will be no review section ahead, and the difficulty will increase sharply, so be prepared!

Data is the lifeblood of spaced repetition algorithms. Collecting appropriate, comprehensive, and accurate data will determine the limits of the capabilities of spaced repetition algorithms.

To accurately estimate a learner's memory states, we need to define the basic behavior of memory. Let's think about it: what are the important attributes of a memory event?

The most basic elements are easy to think of: who (the subject), when (time), and what (memory). For memory, we can explore further: what was remembered (content), how well it was remembered (response), and how long it took (time spent), etc. The response can be further refined by incorporating several grades into the algorithm.

Taking these attributes into consideration, we can use a tuple to record a memory event:

This event records a user's response and cost for a particular item at a certain time. For example:

That is: Jarrett reviewed the word "apple" at 12:00:01 on April 1st, 2022, forgot it, and spent 5 seconds reviewing this flashcard.

With this basic definition of memory events, we can extract and calculate more information of interest.

For example, in spaced repetition, the interval between two repetitions is of critical importance. Using the memory events mentioned above, we can group data by users and items, sort by time, and then subtract the time of two adjacent events to obtain the interval. Generally, to save calculation steps, the interval can be directly recorded in the event. Although this causes storage redundancy, it saves computational time.

In addition to intervals, the historical sequence of feedback is also important. For example, "forgot, remembered, remembered, remembered" and "1 day, 3 days, 6 days, 10 days" can reflect a memory's history more comprehensively and can be directly recorded in memory events:

If you are interested in the data, you can download the open-source dataset from MaiMemo and analyze it yourself.

Now that we have the data, how can we use it? Reviewing the three-component memory model from Day 2, what we want to know are the three attributes of memory states, which our current dataset does not include. Therefore, the goal of this section is to convert memory event data into memory states and figure out their relationships.

The three letters in the DSR model correspond to difficulty, stability, and retrievability. Retrievability reflects the probability of recalling a memory at a certain moment. In probabilistic terms, a memory event is a single random experiment with only two possible outcomes, and its success probability equals retrievability.

Therefore, the most straightforward method to measure retrievability is to perform countless independent experiments on the same memory and then count the frequency of successful recall. However, this method is infeasible in practice because experimenting with memory will change its state, we cannot act as an observer and measure memory without affecting it. (Note: At the current level of neuroscience, it is impossible to measure the memory states at the neural level, so this approach is also unavailable.)

So, are we out of options? Currently, there are two compromise measurement methods: (1) Ignore the differences in the learning material: Both SuperMemo and Anki use this approach; (2) Ignore the differences between learners: MaiMemo uses this approach.

Ignoring the differences in the learning material means that when measuring retrievability, we collect data with the same attributes from the same user, except for the content that the user is learning. While we can't perform multiple independent experiments on one learner and one material, we can do so with one learner and multiple materials. On the other hand, ignoring the differences between learners involves collecting data from multiple learners who are studying the same material.

Considering that the amount of data in MaiMemo is sufficient, this section will only introduce the measurement method that ignores learner differences. After ignoring them, we can obtain a new group of memory events:

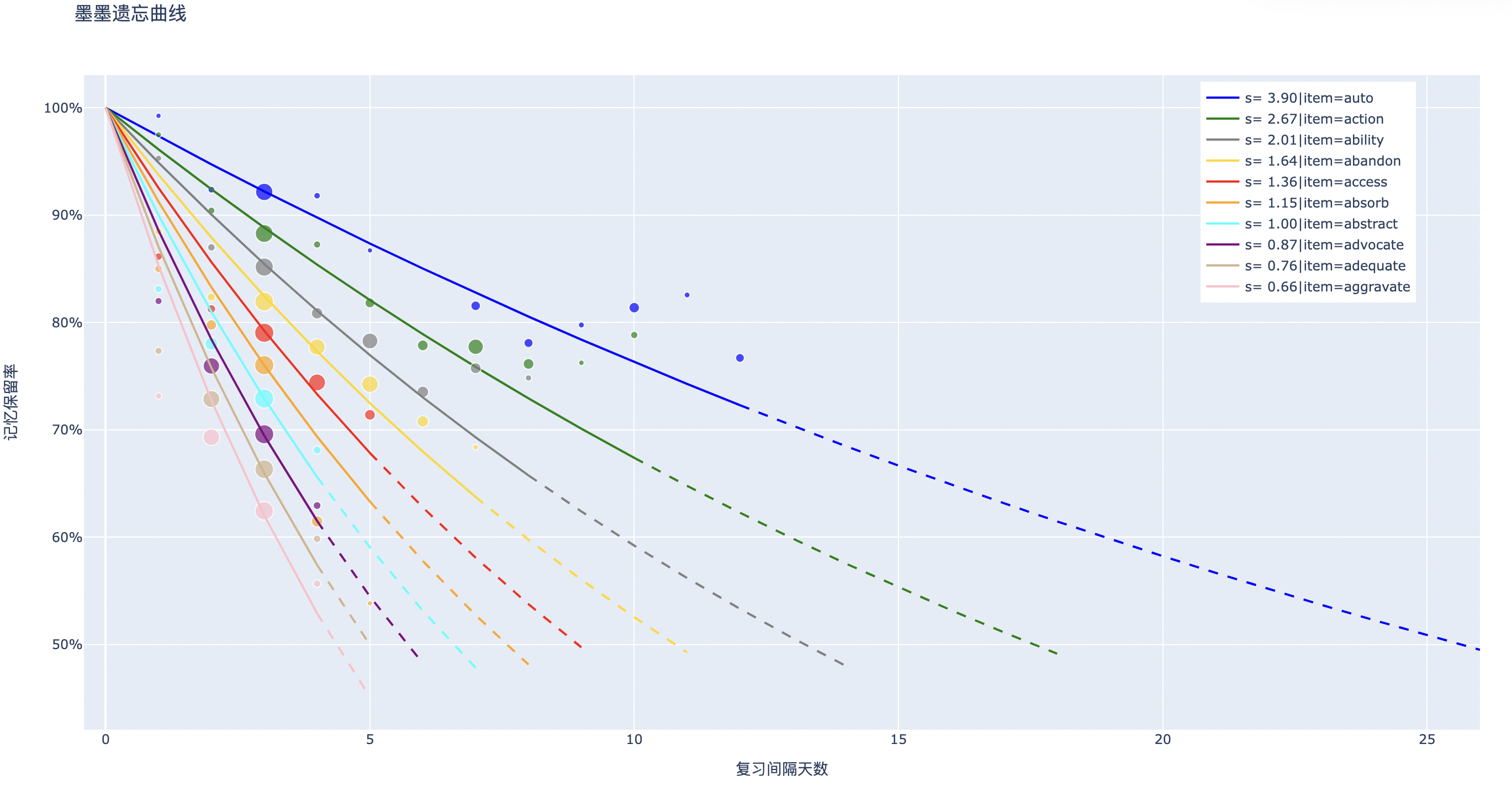

Here, N is the number of learners who have memorized the same material and have the same repetition history. Retrievability

After the retrievability is calculated, the stability can be easily calculated. Based on the collected data, an exponential function can be used to approximate this data and calculate the stability of memory for groups with the same

The scatter plot coordinates are

Finally, it's time to tackle the difficulty. How can we derive the difficulty from memory event data? Let's start with a simple thought experiment. Suppose a group of learners memorizes the words "apple" and "accelerate" for the first time. How can we use memory event data to distinguish the difficulty of the two words?

The simplest method is to test immediately the next day, record the memory event data, and see which word has a higher proportion of successful recalls. Then we can calculate the corresponding value of stability.

That is to say, the stability after the first review can reflect the difficulty. However, there is no standard method for the estimation of difficulty. Since this is an introductory article, the problem of calculating difficulty will not be discussed in detail. Unlike retrievability and stability, both of which have precise definitions, difficulty is a hazy concept.

The rest of this article covers in-depth details about my research works. If you’re new to academics, you can stop here and review the content of the previous three days. If you’re interested in the following content, you can continue reading.

So far, we can transform memory event data into memory states:

Next, we can start describing the relationship between states. What is the relationship between

First, we need to organize the memory state data into a form suitable for analysis:

Here,

In the end, the state data we need to analyze is as follows:

And

We can obtain the relationship formula (the influence of difficulty D is omitted here):

According to the above formula, we can predict the memory state

With the DSR memory model, we can simulate memory states under any review schedules. So, how should we simulate it specifically? We need to start from the perspective of how people usually use spaced repetition software in the real world.

Suppose Jarrett needs to prepare for the GRE in four months and needs to use spaced repetition to memorize the English words for the exam. However, time must also be allocated to prepare for other subjects.

From the above sentence, there are two obvious constraints: the number of days before the deadline and daily learning time. The Spaced Repetition System (SRS) simulator needs to consider these two constraints. In addition, the number of words is limited, so the SRS simulation also has a finite set of cards, from which learners select materials for learning and review every day. The spaced repetition scheduling algorithm manages the arrangement of review tasks. To sum up, SRS simulation requires:

- Material set

- Learner

- Scheduler

- Simulation duration (within a day + total number of days)

The learner can be simulated using the DSR model, providing feedback and memory state for each review. The scheduler can be SM-2, Leitner System, or any other algorithm for scheduling reviews.

Then, we will design a specific simulation process based on the two dimensions of SRS simulation. Obviously, we need to simulate day by day into the future in chronological order, and the simulation of each day is composed of feedback from cards. Therefore, the SRS simulation can consist of two loops: the outer loop represents the current simulated date, and the inner loop represents the current simulated card. In the inner loop, we must specify the time spent on each review. When the accumulated time exceeds the daily learning time limit, the loop is automatically exited, ready to enter the next day.

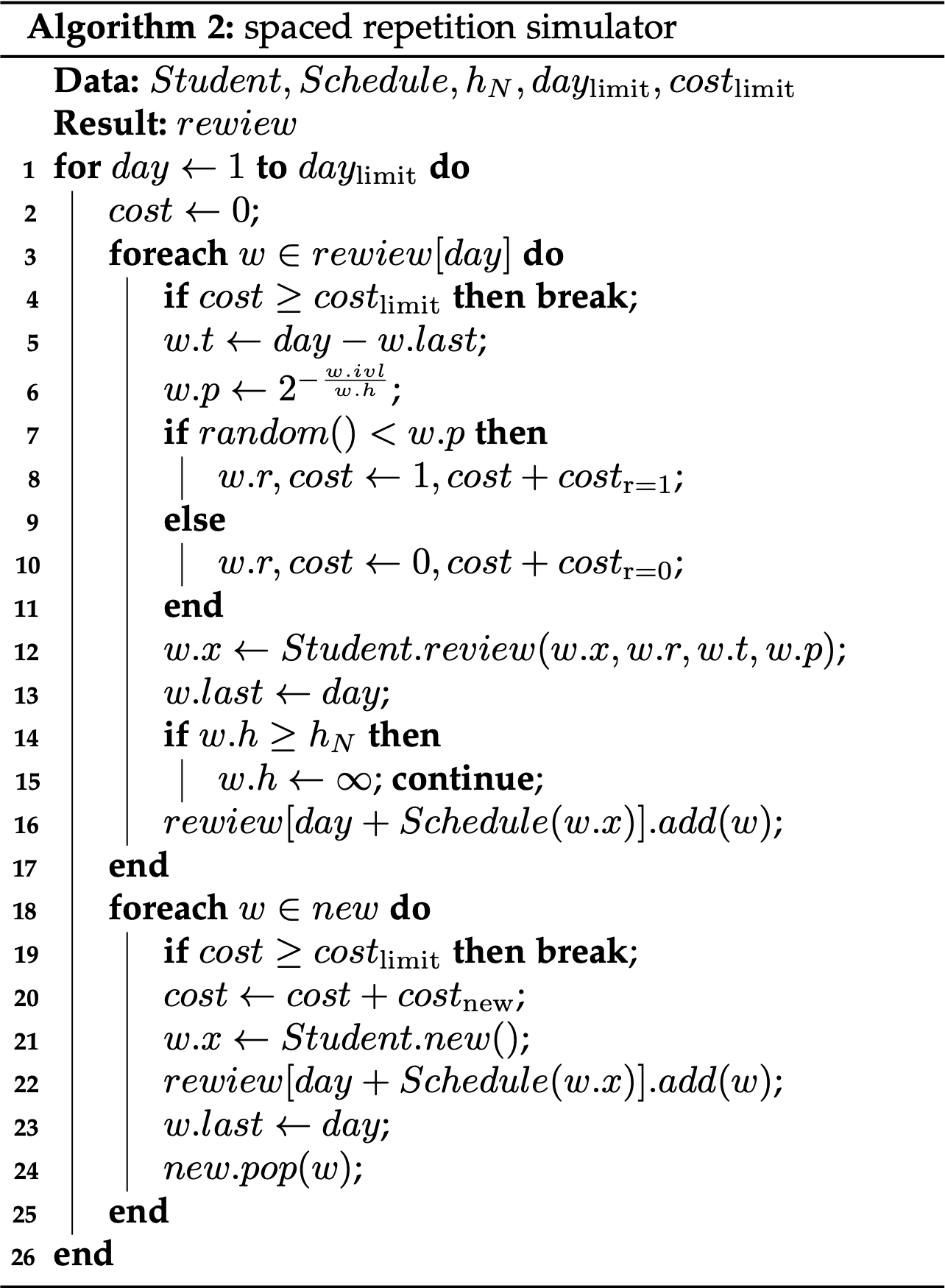

Here is the pseudocode for SRS Simulation:

The relevant Python code has been open-sourced on GitHub for readers who are interested enough to delve into the source code: L-M-Sherlock/space_repetition_simulators: Spaced Repetition Simulators (github.com)

Having discussed the DSR model and SRS simulation, we can now predict learners' memory states and memory situations under given review schedules, but we still haven't answered our ultimate question: What kind of review schedule is the most efficient? How to find the optimal review schedule? The SSP-MMC algorithm solves this problem from the perspective of optimal control.

SSP-MMC is an acronym for Stochastic Shortest Path and Minimize Memorization Cost, encapsulating both the mathematical toolkit and the optimization objective underpinning the algorithm. The ensuing discourse is adapted from my graduate thesis, "Research on Review Scheduling Algorithms Based on LSTM and Spaced Repetition Models," and the conference paper A Stochastic Shortest Path Algorithm for Optimizing Spaced Repetition Scheduling.

The purpose of any spaced repetition algorithm is to help learners form long-term memories efficiently. Whereas memory stability measures the storage strength of long-term memory, the number of repetitions and the time spent per repetition reflect the cost of memory. Therefore, the goal of spaced repetition scheduling optimization can be formulated as either getting as much material as possible to reach the target stability within a given memory cost constraint or getting a certain amount of memorized material to reach the target stability at minimal memory cost. Among them, the latter problem can be simplified as how to make one memory material reach the target stability at the minimum memory cost (MMC).

The DSR model satisfies the Markov property. In the DSR model, the state of each memory depends only on the last stability, the difficulty, the current review interval, and the result of the recall, which follows a random distribution based on the review interval. Due to the randomness of stability state transition, the number of reviews required for memorizing material to reach the target stability is uncertain. Therefore, the spaced repetition scheduling problem can be regarded as an infinite-time stochastic dynamic programming problem. In the case of forming long-term memory, the problem has a termination state, which is the target stability. So it is a Stochastic Shortest Path (SSP) problem.

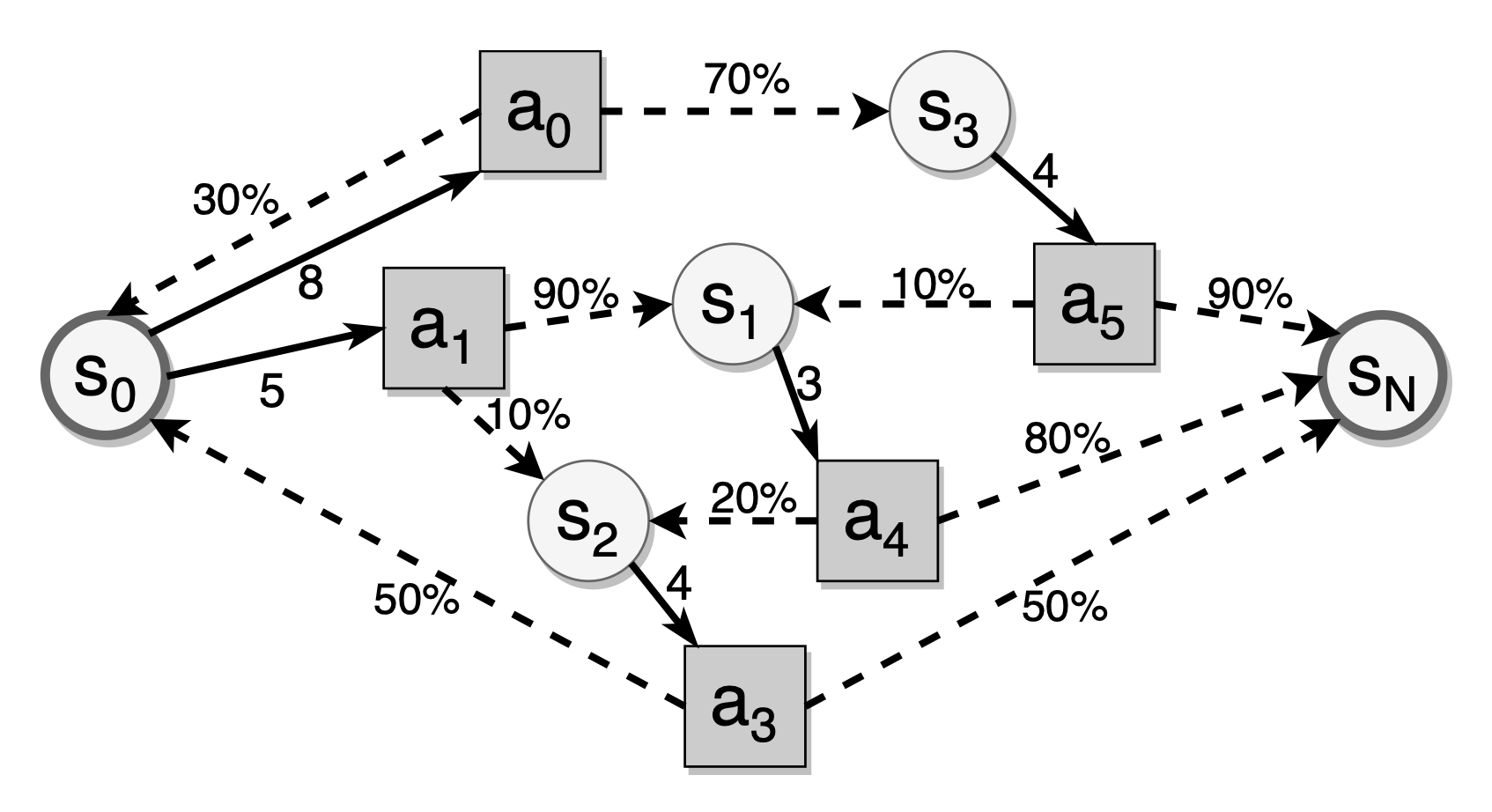

As shown in the above figure, circles are memory states, squares are review actions (i.e., the interval after the current review), dashed arrows indicate state transitions for a given review interval, and black edges represent review intervals available in a given memory state. The stochastic shortest path problem in spaced repetition is to find the optimal review interval to minimize the expected review cost of reaching the target state.

To solve the problem, we can model the review process for each flashcard as a Markov Decision Process (MDP) with a set of states

The state-space

where the

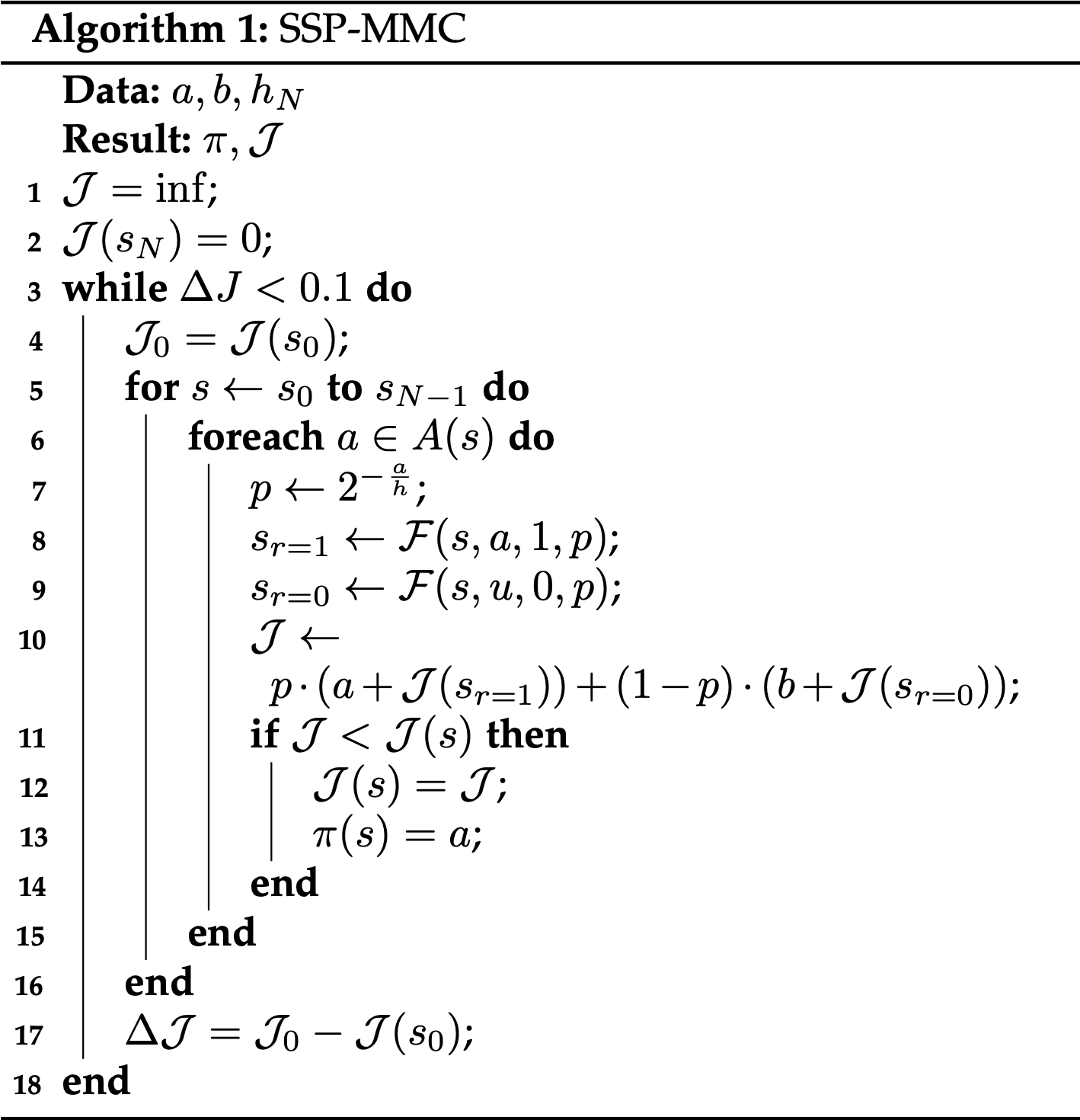

We solve the Markov Decision Process

where the

Based on the above Bellman equation, the Value Iteration algorithm uses a cost matrix to record the optimal cost and a policy matrix to save the optimal action for each state during the iteration.

Continuously iterate through each optional review interval for each memory state, compare the expected memory cost after selecting the current review interval with the memory cost in the cost matrix, and if the cost of the current review interval is lower, update the corresponding cost matrix and policy matrix. Eventually, the optimal intervals and costs for all memory states will converge.

In this way, we obtain the optimal review policy. Combined with the DSR model for predicting memory states, we can arrange the most efficient review schedule for each learner using the SSP-MMC algorithm.

This algorithm has been open-sourced in MaiMemo's GitHub repository: maimemo/SSP-MMC: A Stochastic Shortest Path Algorithm for Optimizing Spaced Repetition Scheduling (github.com). Readers interested in an in-depth examination are encouraged to fork a copy for local exploration.

Congratulations on reaching the end! If you haven't given up, you've already entered the world of spaced repetition algorithms!

You may still have many questions, some of which may have answers, but many more are unexplored areas.

My capacity to address these questions is severely limited, yet I am committed to dedicating a lifetime to advancing the frontiers of spaced repetition algorithms.

I invite you to join me in unraveling the mystery of memory!

History of spaced repetition - supermemo.guru

Original link: https://l-m-sherlock.github.io/thoughts-memo/post/srs_algorithm_introduction/

My representative paper at ACMKDD: A Stochastic Shortest Path Algorithm for Optimizing Spaced Repetition Scheduling

My fantastic research experience on spaced repetition algorithm: How did I publish a paper in ACMKDD as an undergraduate?

The largest open-source dataset on spaced repetition with time-series features: open-spaced-repetition/FSRS-Anki-20k